Imagine this: you’re a student scurrying in a last-ditch effort to cram in some TeoChew before a year-planned trip to the homeland – half pronounced, barely remembered. As you browse through piles of “Ni Shuo Ya” textbooks and Mandarin scriptures, you notice that none of them contain any TeoChew.

This is the reality for younger generations living not only in Singapore, but all over the world. The language of our grandparents is slowly melding into a faded background, in which mandarin is the bold title font. Individual effort is not enough to revitalize years of rich history.

Why are dialects disappearing?

There’s no easy answer. Learning a lost centuries-old dialect requires constant practice and exposure, which is hard to find in Singapore. While the globalization of mandarin has secured smooth communication throughout generations and communities, it has also served as a springboard for younger generations to be ignorant of the language of their ancestors.

It seems that teaching children of their cultural heritage is useless when we can settle for something more accessible and “practically the same”. Sounds about reasonable! However, this soon becomes a flaw at grandma’s house during a chinese new year dinner, when parents scramble to play translators for even the smallest exchanges between children and elders.

A simple comment “Why don’t you teach him Cantonese la?” stirs a familiar guilt.

Language is more than just a tool; it’s a practice. It can’t be preserved by just a few families among millions. It should be a community effort that connects different identities.

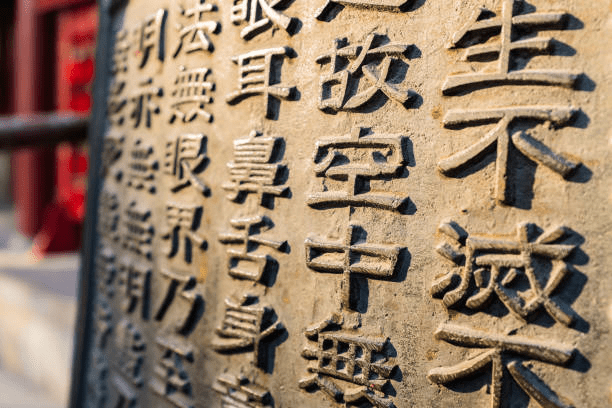

How can we assure that a dialect is passed down if its prevalence is no longer valuable? If the capability to communicate, for the most part, is already fulfilled? This way of thinking is heavily inaccurate. A dialect embodies centuries of historic value and cultural identity, transcending the mere idea of communication.

In Singapore, for years, Hokkien had been the dominant Chinese dialect. However, the rates of Hokkien users are declining significantly due to many reasons, media exposure, day to day effectiveness, mandarin influence… The result is a slow erasure of not just vocabulary, but of cultural memory.

According to Singstats, in 2020, mandarin was the second most spoken language in Singapore at 30% whereas other Chinese dialects combined barely make it past 10%.

Simply accepting the loss of a dialect is like waving goodbye to fragments of your identity. Small puzzle pieces that shaped you, your parents and the way you were raised. It’s like skipping the introduction to a video game – not the most useful addition, but it unravels a whole layer of deeper complexities which help you understand a character’s current predicament.

Without it, the narrative of who you are feels incomplete.

What can we do?

The question shifts from “why” to “how.” With our limited knowledge, lack of resources, and unmotivated friends, how can we revive a lost dialect? Take Hebrew, for example. For nearly 2,000 years, it was nearly extinct. Yet, through community efforts, it made a comeback.

Hebrew books flooded the market, and institutions were created to teach it in schools. So, what sets Hebrew apart from Chinese dialects? The answer lies in collaboration and constant practice—frequent exposure to the language. To make this possible, we must instill these values in our children

So, while the internalization of mandarin is undeniable, we can still create a well-rounded society where each dialect is practiced,

6/4/2025

Leave a comment